Sole Systems 006: Biomimicry

Learning From The Natural World

We take a deep dive into the role that the natural world has played in the development of footwear design, investigating naturally occurring examples that designers have looked to for guidance in solving human problems. Looking at how creatures across the planet clad their lower limbs and the ways in which designers can use this to inspire material and structural innovation in footwear production. Afterall, there is no better designer than nature itself.

Biomimicry, in its simplest terms, is a design philosophy which looks to the natural world to find solutions for complex human issues, harnessing the expertise of organisms and ecosystems that have been developed through thousands of years of evolution and natural selection. Biomimicry has been widely used not just in product design but more commonly in the design of transport, architecture, computers, and even agricultural and city planning.

Hook and loop tape, for which the brand Velcro has become ubiquitous, is a household and footwear mainstay which is probably the most recognisable instance of biomimetic design. George de Mestral was a Swiss engineer who, when out for a walk in 1941, noticed that burrs would stick to his woollen clothes as well as his dog. Upon closer inspection he realised that the tiny hooks of the burr adhered to the loops of fabric which sparked the inception of Velcro®. Hook and loop tape provides us with an example of just how important biomimicry is within footwear design. It’s often easy to overlook what has gone into designing something when you use it every day which is why “good design is invisible”.

The Nike Air Terra Goatek and the original Nike Mayfly both serve as examples of biomimicry in footwear design, in form and function. The Goatek takes its formal inspiration from the hooves of mountain goats whereas the function of the Mayfly takes its design cues from the short lifespan of its namesake aquatic insects.

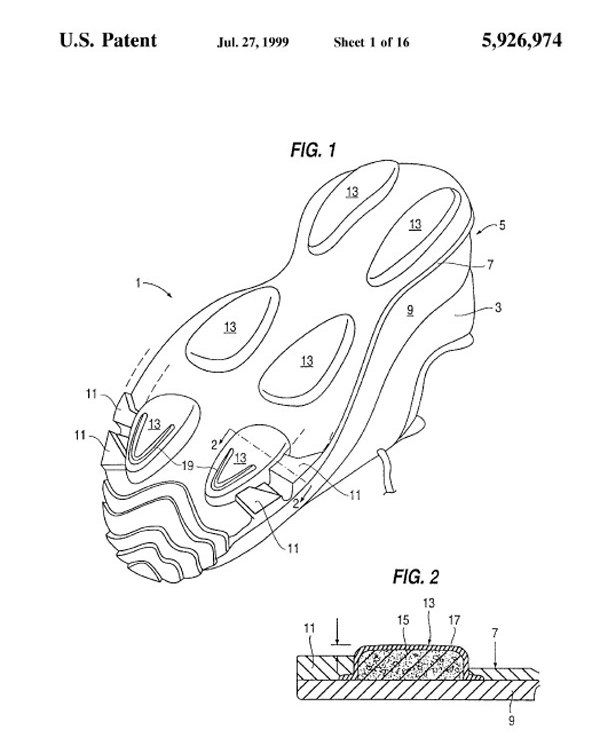

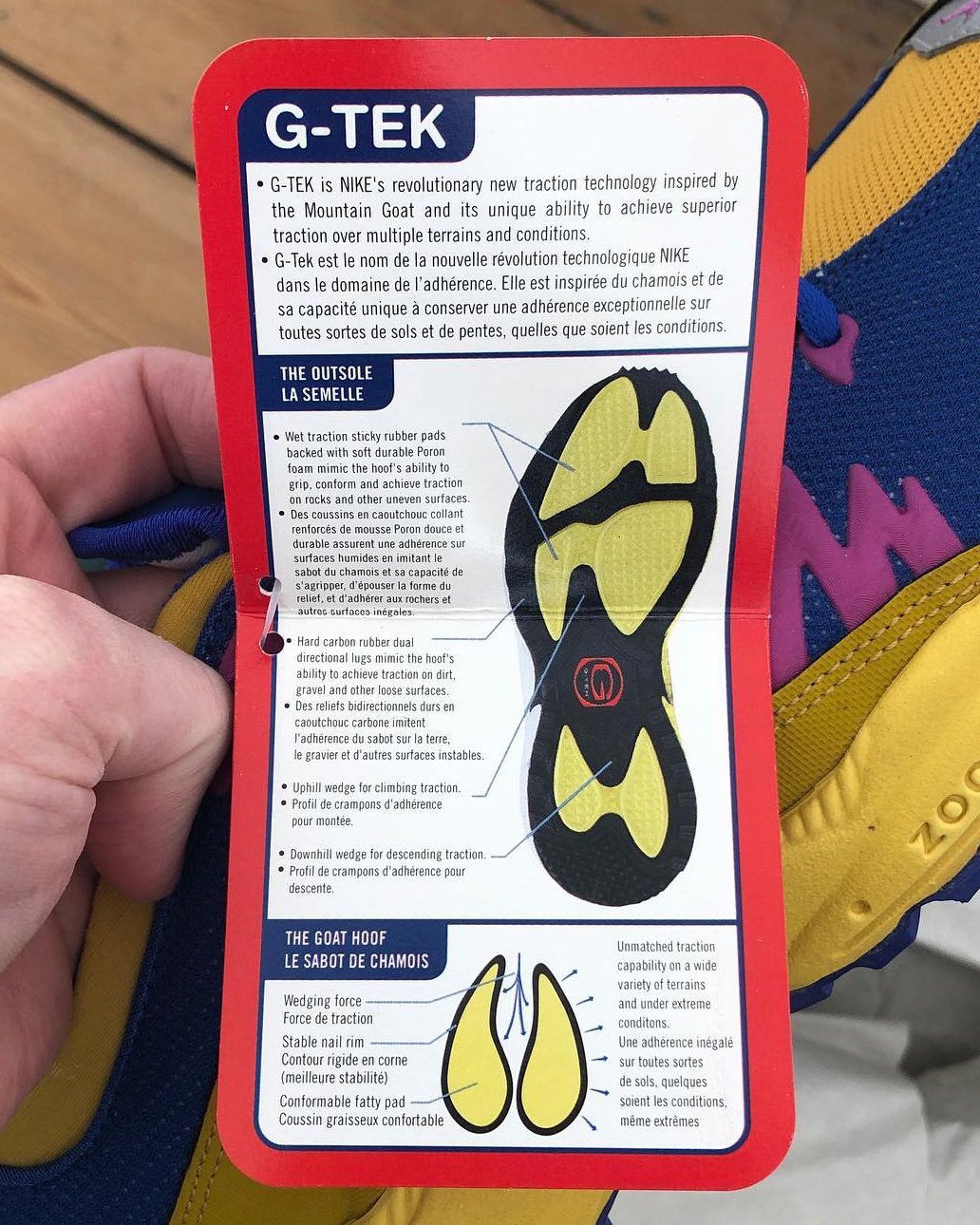

The Nike Air Terra Goatek utilises G-Tek traction technology inspired by the cloven hooves of the Mountain Goat, a surefooted mammal which is known for its traction over the steep and rocky mountain façades of Northern America. Unlike other hooved animals the Mountain Goat has two front facing toes which are soft on the bottom and surrounded by a hard edge, supported by two small rear toes. The soft sole provides traction on uneven terrain and the hard edge provides a cupping action which prevents the hoof from sliding, the two smaller toes to the rear can be spread-out to enhance uphill and downhill traction. The G-Tek sole closely mimics the evolutionary make up of a Mountain Goat hoof, wet traction rubber pads backed with Poron foam mimic the goats ability to find grip on uneven terrain while the hard carbon rubber surrounds the perimeter of the sole to ensure no slippage on loose surfaces. The original tags for the Nike Goatek feature a side-by-side comparison of the hoof of a mountain goat and the G-Tek sole, proving the extent to which the technology took its inspiration.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is the Mayfly, where the Goatek has been designed to offer functionality through durability the Nike Mayfly offers functionality through fragility. While we may commonly believe that good design means longevity, Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman was more concerned with creating a race shoe with as little excess weight as possible, a running shoe that was designed to last no longer than the length of a race. Nike continued the design ethos set out by Bowerman and started work on a running shoe that was designed to last just 100k, a shoe that could quite literally be run into the ground. After much experimentation the Mayfly upper was constructed using an ultralight ripstop with perforated synthetic suede overlays while the sole was constructed from Nike’s patented Phylon with expanded air pockets within the foam to create a lighter, more transient sole. The final product weighed just 135g and came accompanied with a bag to return the inevitably destructed pair back to Nike for recycling.

Kihachiro Onitsuka was famously inspired by an octopus salad bowl to design the Onitsuka Tiger suction cup basketball shoe used by the Japanese basketball team at the 1956 Olympic games, utilising a bottom sole inspired by the suction cups of an octopus for increased grip. Another famous example is the Cheetah Blades that we explored in our previous Sole Systems, a prosthetic leg based on the hind legs of the Cheetah for increased speed for Paralympic athletes. These examples illustrate how biomimetic design utilises years of evolution from the natural world to create products with distinct purpose and practicality.

Footwear designers don’t just look to nature for structural design influence but have increasingly looked to the natural world to advance material development. In a world that has become increasingly more eco conscious there is more pressure put on contemporary designers to create alternatives that are less harmful to the planet. The footwear industry relies heavily on a host of manmade materials and plastics to protect our feet but many footwear designers are seeking to change the norm by creating shoes made from natural materials to produce biodegradable shoes that will leave little to no trace of their existence in years to come.

Sneature, created by material designer Emilie Burfeind is a completely biodegradable trainer, utilising just three bio-based materials to create a sneaker which can be recycled or even composted at the end of its life. Whereas conventional trainers contain hard plastics, woven synthetic fabrics, and even up to 110g of rubber, Sneature utilises mycelium, chiengora, and natural rubber. Using mycelium; a far-reaching fungal structure used to create artificial leather, paired with Chiengora which is a yarn spun from dog hair, and 6 grams of natural rubber, Burfeind has created a sleek and seamless trainer equipped for all the trappings of daily urban life. Chiengora is 42% more effective at retaining heat than sheep’s wool and was widely used by Indigenous people in the Pacific Northwest while the mycelium is mixed with agricultural waste product to create the inner and outer sole. Burfeind predicts that the shoes can be worn for a period of two years before becoming too worn by which time the shoe can be completely recycled.

Likewise, New York based brand Public School teamed up with scientist Dr. Theanne Schiros to create a shoe constructed from leather produced in a lab using the bacteria usually associated with Kombucha, SCOBY. The project aims to use waste as a regenerative resource to create a product which, like the Sneature, is completely compostable. The “bio-leather” shoe is created using the lowest carbon footprint possible, the SCOBY used is made from scratch using tea and sugar or sourced from a local Kombucha brewery in a circular waste-to-resource process. All elements of the shoe, including the laces, are produced from the bi-leather and has a 97% lower carbon footprint than synthetic polyurethane leather. These two practices highlight that the footwear industry can do more than just look to different structures within nature to find inspiration, but can also design with nature in mind.

The Vibram FiveFingers have amassed something of a cult following and are by far some of the most unique looking shoes on the market. Vibram didn’t look to another species to find their solution for the human foot but actually respect the foot as a piece of evolutionary engineering in its own right. Instead of attempting to redesign the human foot, the FiveFingers act as a reinforcement of what is already a pretty remarkable piece of biomechanical design. The model has been most commonly adopted by marathon runners as the human foot has evolved to be the ideal structure for running long distances. Understandably, the Vibram FiveFinger has long been a fashion outsider due to its unique design focus which highlights the natural form of the foot rather than enclosing it, recent collaborations with Balenciaga, however, have showcased the FiveFinger in a completely new light. Complete with a heel similar to Balenciaga’s signature X-Pander the Toe Boot shoe cuts a sleek but technical silhouette and looks like something you might otherwise see in a Ridley Scott film.

German designer and architect, Stephan Henrich, who we have previously featured on CONCEPTKICKS, has designed a more conceptual approach to the issue of reinforcing the human foot. His “CRYPTIDE” concept shoe aims to work with the foots natural ability rather than against it, providing a 3D printed shoe which increases traction and suspension without rendering the foots natural qualities obsolete. Most importantly, these shoes look otherworldly and provide an exciting vision of what shoes could look like in the future.

Other, more wearable approaches to minimalist shoe design can be seen in the Camper Karst or even the beloved tabi silhouette most famously deployed by Margiela. The Karst at first glance is an unassuming silhouette that features a bulbous, ergonomic outsole which is based on the contours of a human foot, while the design is nothing more than a stylistic choice it is interesting to see how the biology of a human foot can be used to influence the design of an otherwise ‘normal’ looking shoe. While the Margiela Tabi Boot is widely accepted as the model that popularised the tabi silhouette to the Western world, the style actually dates back as far as 15th Century Japan and was first deployed as a sports silhouette by ASICS in 1953 with the ONITSUKA Marathon Tabi, designed to promote a more fluid and natural running motion by freeing up the movement of the big toe.

The natural world offers an abundance of weird and wonderful foot-centric phenomena which is begging to serve as inspiration for footwear designers in much the same way they did for the Nike Mountain Goats and Mayfly’s. The scaly-foot snail looks like it may have taken inspiration from a Medieval Knight, but its protective iron armour formed deep in the Indian Ocean is actually a result of the snails’ proximity to hydrothermal vents on the sea floor. This snail is the only known animal to incorporate iron armour into its exoskeleton which is built using the iron-rich hydrothermal water to protect itself from potential predators.

These images were taken by photographer Steve Gschmeissner and shortlisted for the 2016 Royal Photography Society International Images for Science contest; they depict the foot of a mosquito using a scanning electron microscope. It’s hard to believe that this image doesn’t depict an otherworldly being, rather something of a daily annoyance for humans across the globe. While it’s difficult to glean any useful information from this image for the untrained eye, the mosquito foot seems to include a claw, scales, and a pulvillus – which could be the function that enables the insect to land on water. So, who knows? Maybe if we continue to further our understanding of nature through biomimetic design, we could be walking on water before you know it.