Surface Tension : Part 01

BRIEF HISTORY OF RUBBER TECHNOLOGY

Hobnails to Sticky

(1930 - 1979)

Written by Leah Balagopal

Surface Tension is a series about rubber technology in climbing, tracing traction from nature’s first templates to the chemical age. Part 1 begins when rubber entered the story and rewired what footwear could do. Climbers soon discovered that sensitivity underfoot was its own kind of safety, and the sport began demanding friction as a feature. This chapter starts at the hinge point, when tragedy met necessity and new materials reshaped how people moved through the mountains.

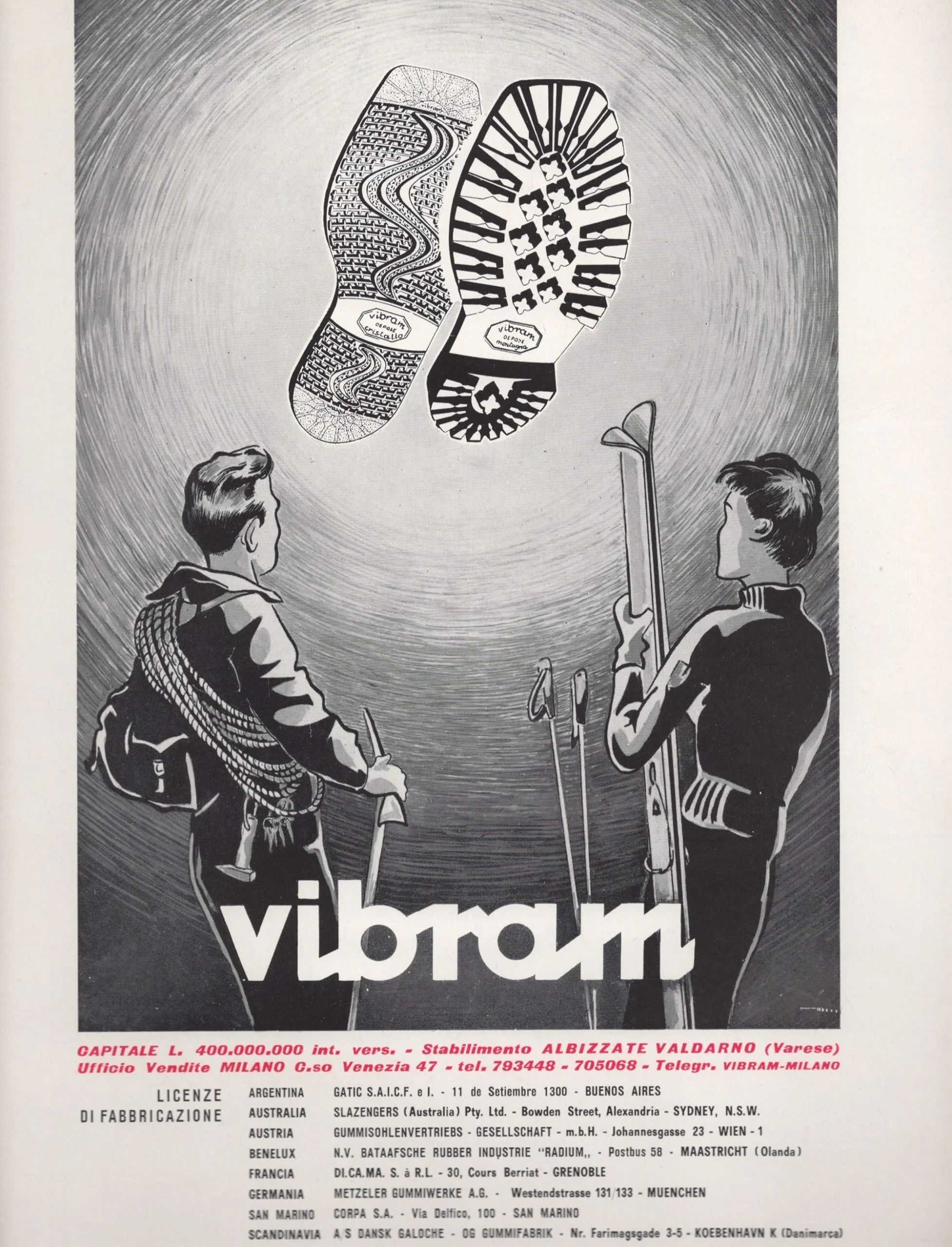

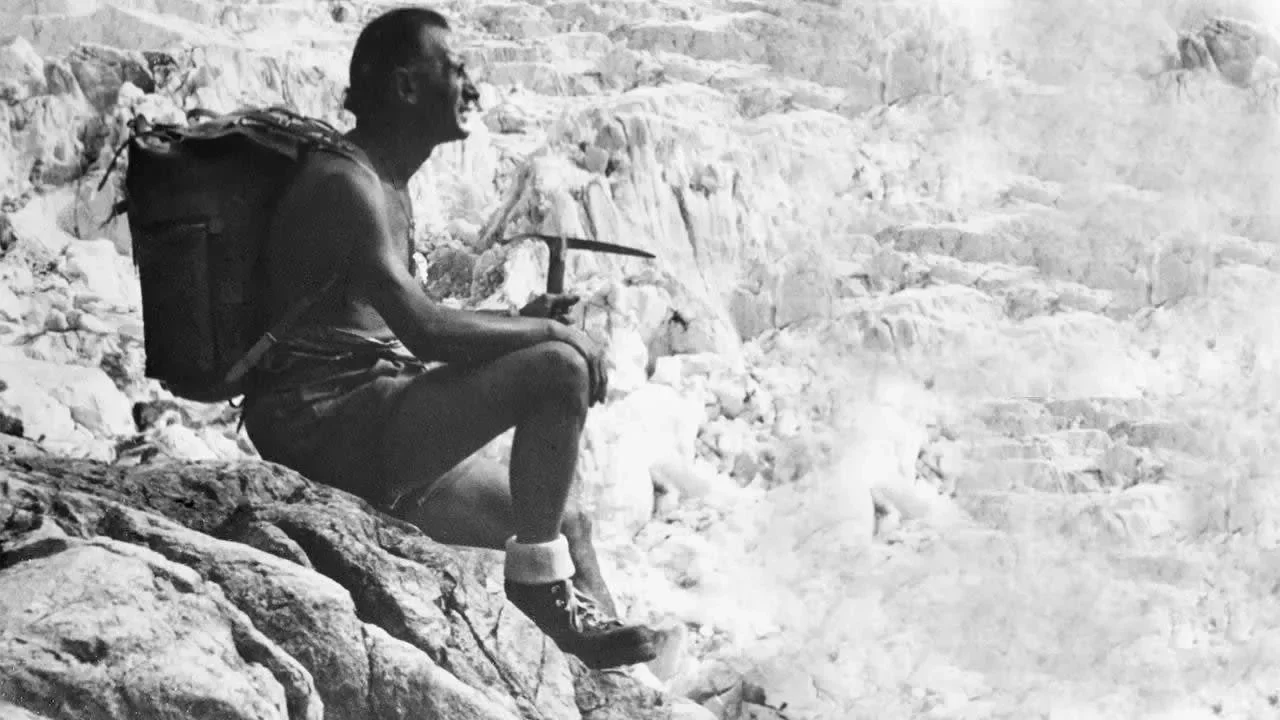

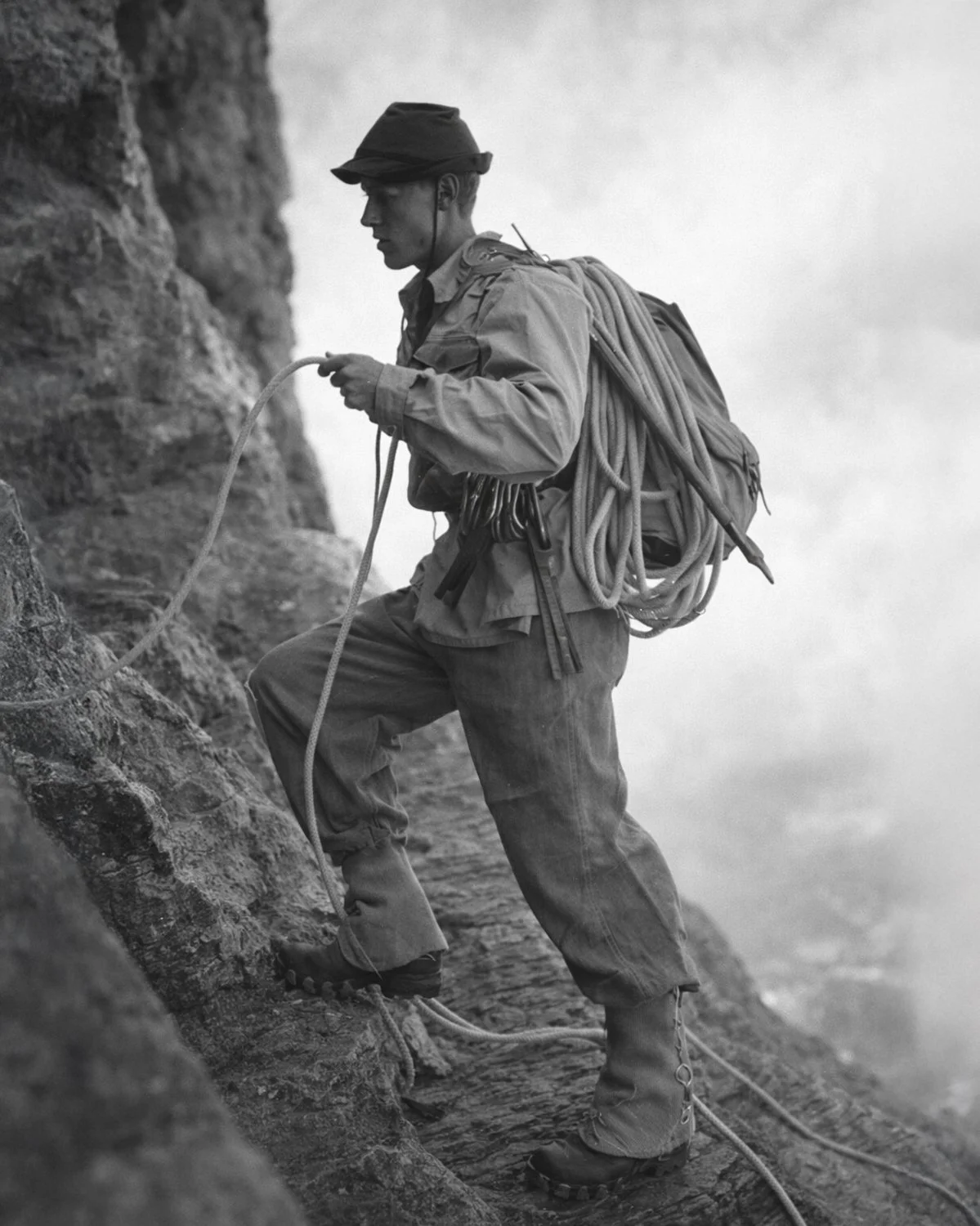

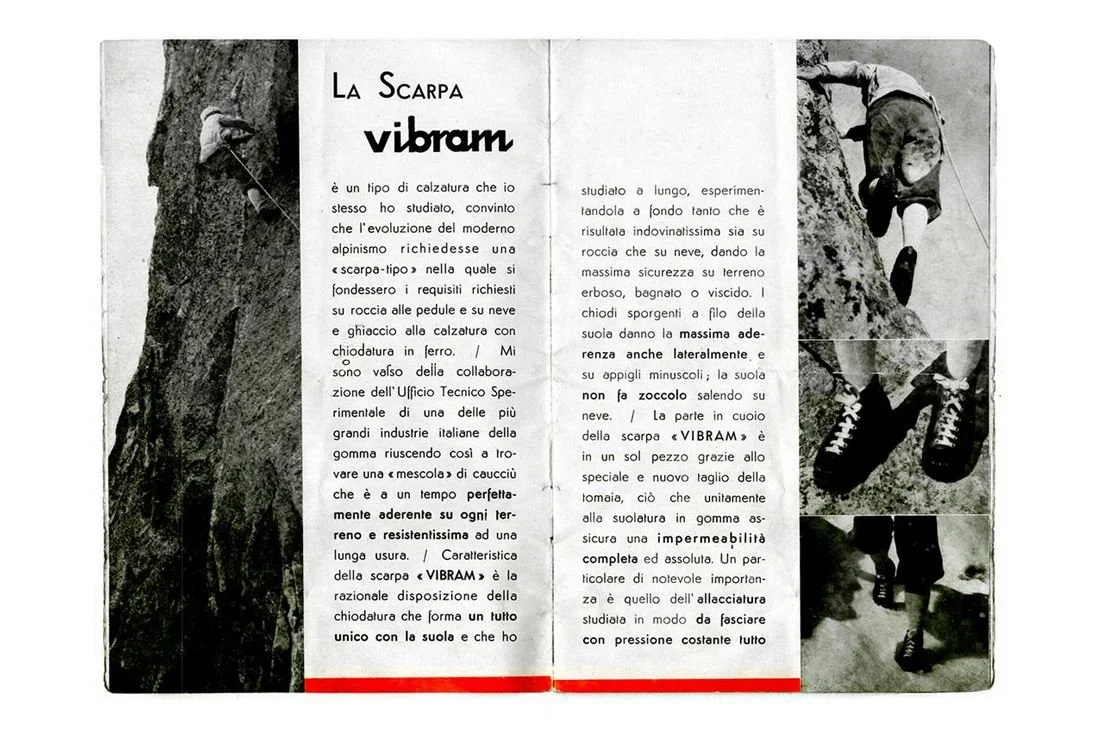

In September 1935, a team of 19 climbers from Milan set out to climb the South West Ridge of Punta Rasica, among them was Vitale Bramani. When snow and heavy fog swept in, six members of that expedition never returned. The tragedy pushed Bramani to rethink what a climbing sole needed to be. He wanted the kind of predictability the mountains rarely grant and grip that remained dependable in unstable conditions. He needed traction that didn’t vanish when rock slicked over or fresh snow settled in. That determination led to the creation of what would become the Vibram Carrarmato sole, a lugged rubber system engineered for survival as much as for mobility. His idea might have stayed a workshop curiosity if not for Leopoldo Pirelli, who saw potential in Bramani’s prototypes and backed him with the rubber expertise of Pirelli Tyres. What had begun as tire tread logic focused on load distribution and debris shedding void channels, was reshaped into something meant for the human foot. Nearly ninety years later, Vibram is still the default language of traction because it solved a problem that never went away.

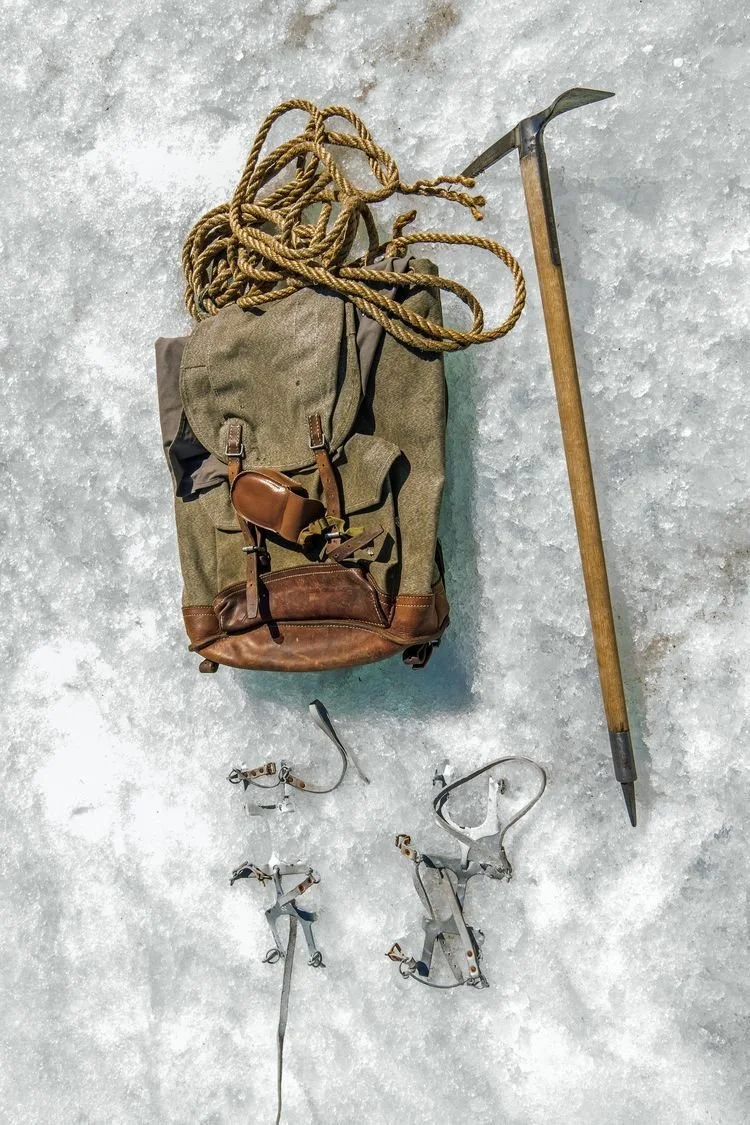

The first Carrarmato sole was not simply rubber replacing leather. It was a structural system, three dimensional lugs arranged to create biting edges and self-cleaning voids that give snow and grit somewhere to go instead of packing into a slippery layer. The perimeter crown lugs nodded to the old mountain boot tradition of bite and durability, a direct echo of the hobnailed soles once hammered into leather and wood. The central lug carried an even deeper lineage. What began as a decorative motif was reinterpreted into something functional, its shape recalling the patterned flooring of Milan’s Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, a passage Bramani walked daily on his way to CAI (Italian Alpine Club) and SEM (Milanese Hiking Society). It also subtly evoked the summit crosses scattered across the Alps. The Carrarmato was performance built from memory, a design that carried tradition forward while solving the problems the mountains had exposed. Vibram describes the early Carrarmato as a carefully designed compound mix, built to balance rigidity, abrasion resistance, and grip, and made possible by vulcanization, the heat driven chemical process that adds crosslinks between rubber molecules and transforms soft, unstable raw rubber into a durable, elastic material, technology that was advanced for the 1930s.

Yet even as the materials grew more refined, there were no laboratory benchmarks or industry norms to measure performance. Before modern standardization, there was only field proof. "Field testing has always been a cornerstone of Vibram’s development process, and it still is today," Vibram says. "From the very beginning, these trials played a crucial role in product evolution–just consider that Vitale Bramani personally tested the first sole for an extended period under real conditions." This was testing when failure had large consequences. "Even today, in the absence of reference standards that cover all aspects of soles, Vibram’s internal know-how remains essential to ensure performance and quality."

Yet for all the ingenuity in tread design and field testing, rubber was still the bottleneck. The mountains demanded more than the materials of the 1930s could consistently give. And then, almost abruptly, the world forced a leap. When the Second World War disrupted global rubber supplies, industrial chemists scrambled to create synthetic alternatives. Although discovered earlier, compounds like neoprene, butyl, and styrene-butadiene were now being pushed into mass production. They were refined and engineered to withstand temperature swings and abrasion far better than raw latex. Once peace returned, those compounds trickled into civilian use, influencing footwear as much as they had aviation and automotive design. Bootmakers began experimenting with blends that resisted cracking at altitude. The post-war boom in chemical manufacturing quietly gave craftsmen and innovators a new vocabulary of materials.

Rubber technology at the time was still built around durability, not friction. These hard compounds were meant to last for years, relying on edges and lug geometry to grip rock and snow rather than any kind of molecular adhesion. The idea that soft rubber hadn’t arrived yet. Traction changed mountaineering fast. It began appearing on alpine boots from Galibier, La Sportiva, and Scarpa, dense, durable soles built for crampons and rocky terrain, though still far from the sensitivity rock climbers would later demand.

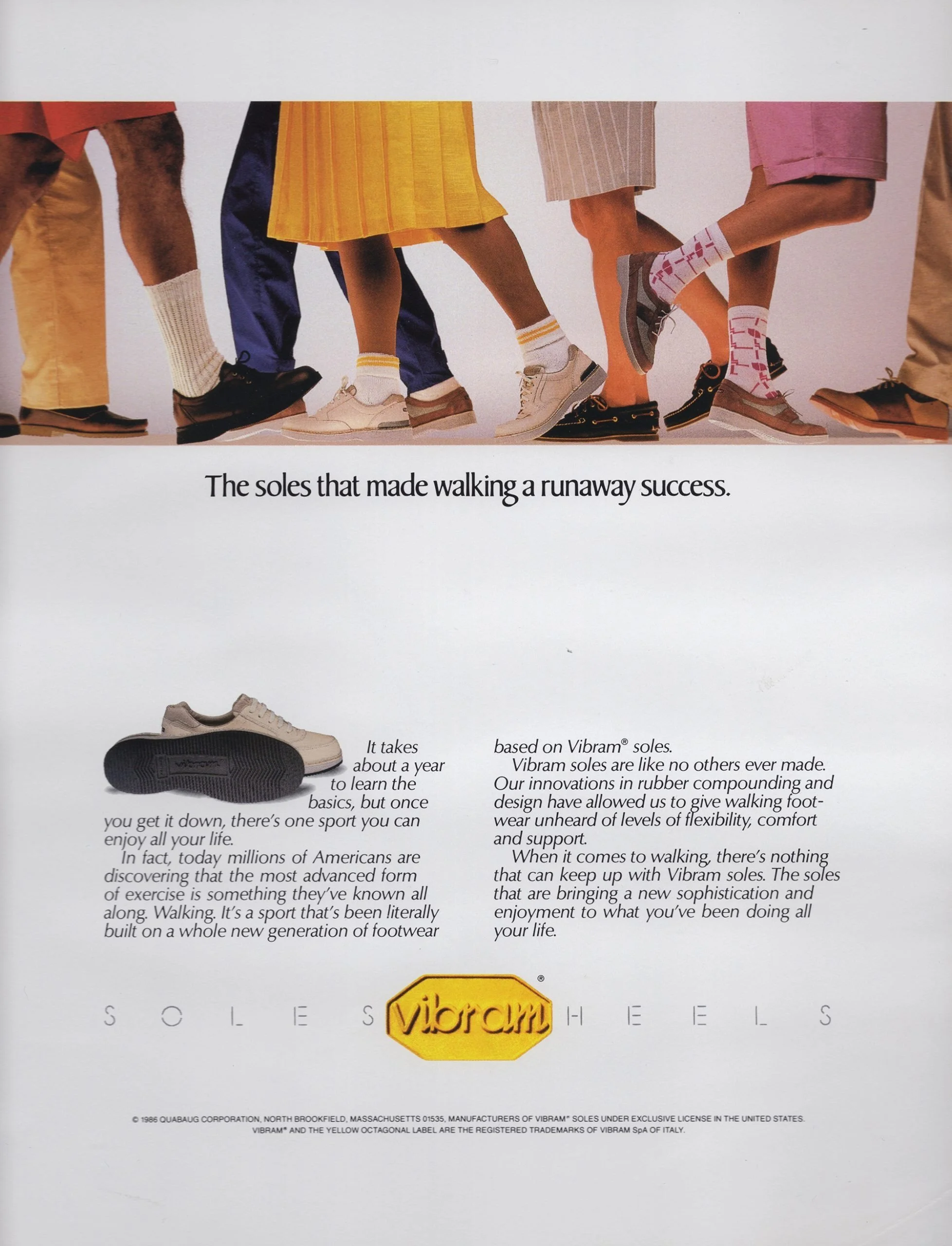

From there, the Carrarmato continued to evolve, spreading in different directions. Its design radiated outward into expedition boots and, steadily, into new markets, and by 1969 the debut of the yellow octagonal badge would make its stamp on history.

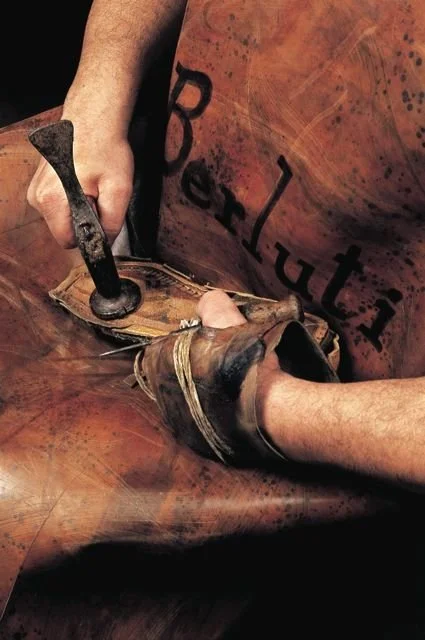

But it also spread inward into a practice that now feels almost old-fashioned, repair. A good leather upper can outlive multiple soles, with the outsole being sacrificial. The Carrarmato made the sole a replaceable component rather than a doomed foundation, strengthening a long standing cobbler culture. Boots were kept in service instead of disposed of at the first sign of wear. This was the original circular thinking, the belief that equipment deserved a second life, not a landfill, and that the true test of a design was whether it could be repaired, not replaced.

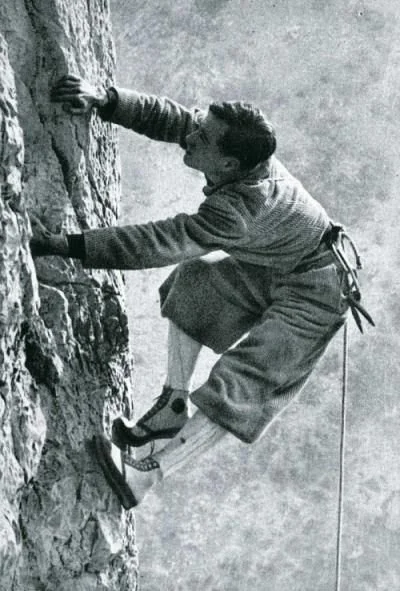

That philosophy, as much as the product itself, helped carry Vibram beyond the Alps. Although Vibram mostly held the mountaineering line through these decades, its influence was already international. Expanding reach didn’t mean the chemistry stood still, the material itself continued to evolve. Vibram’s own perspective is that true high grip climbing compounds emerged only once rubber chemistry advanced enough to tune crosslink density, filler systems, and curing parameters, creating softer, higher-hysteresis rubbers that could generate friction through controlled deformation rather than lug geometry alone. Comparing old and new recipes head-to-head isn’t straightforward because each was engineered for a different job. Even lug height, Vibram notes, was never one universal pattern but tuned by application from the beginning. And yet, for all those refinements, the core Vibram design logic and visual language has remained constant. Tweaked over the years but never replaced, it has become shorthand for quality and proof that the best designs are kept alive because they work. But while mountaineering traction continued to refine the lug, a different idea was taking shape on the rock itself. European craftsmen like Pierre Allain introduced smooth soled rock shoes. What became known as PA's used thinner, more flexible rubber that felt closer to the stone even if it still wasn’t climbing specific in the modern sense. That idea didn’t stay isolated. Edmond Bourdonneau (EB) largely picked up what Allain had already worked out, turned it into a commercial product, and then pushed it further by introducing some of the first molded rock shoes. Less a clean break than a practical continuation of a form that had already proven itself on the rock.

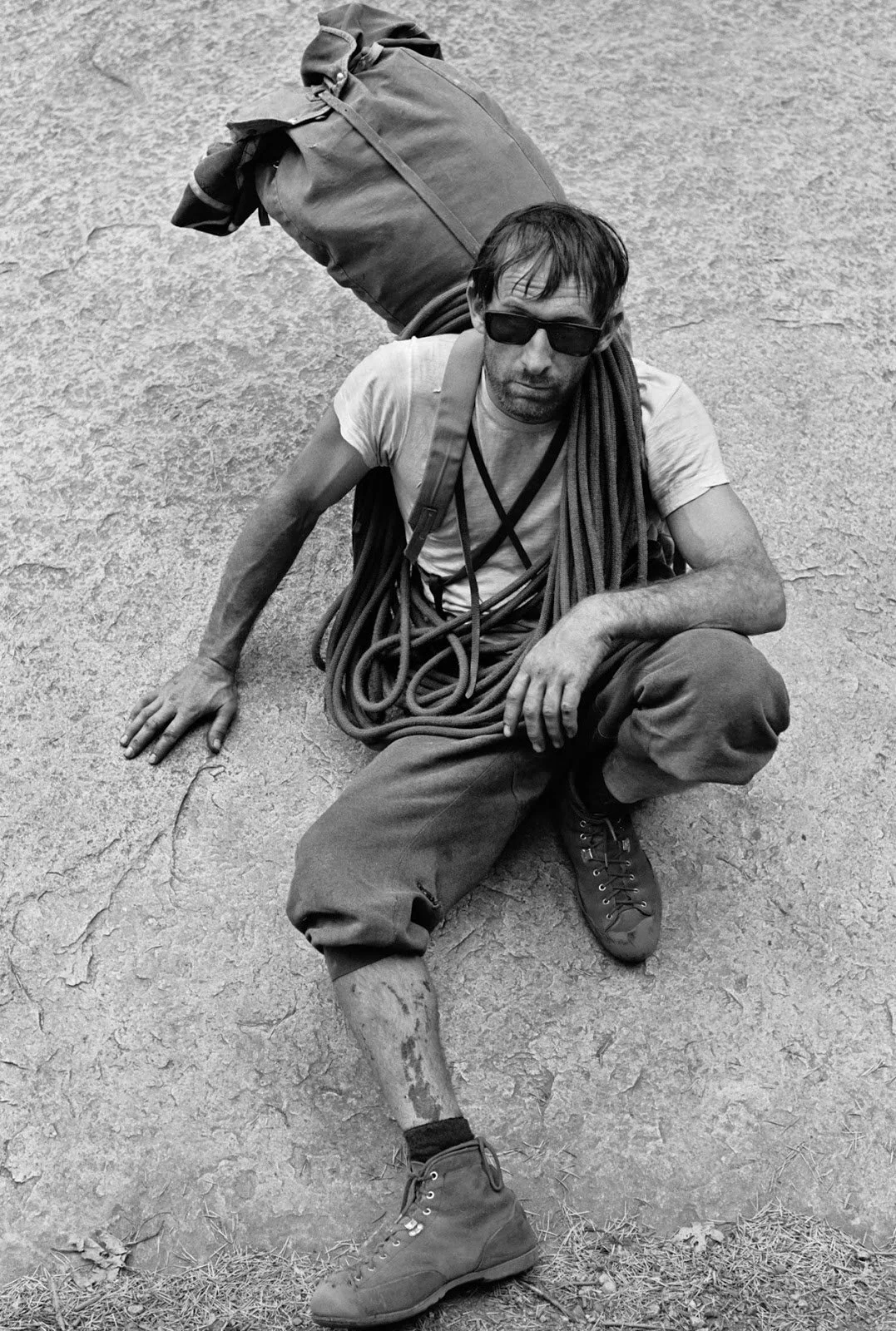

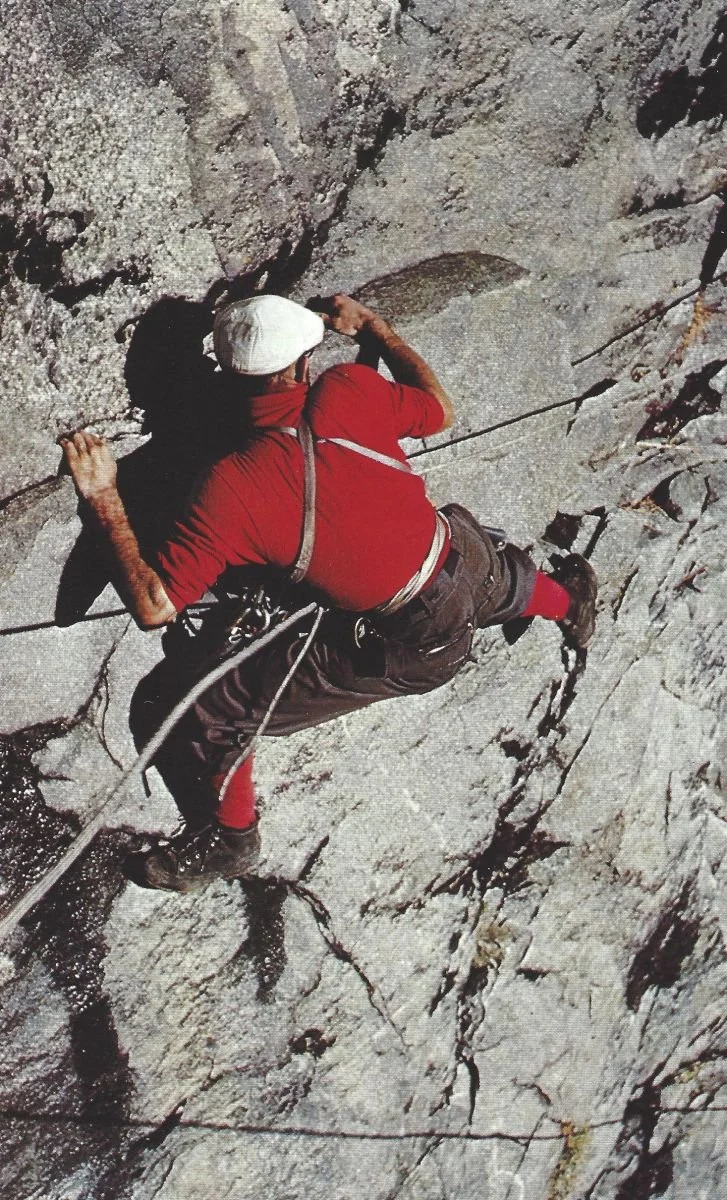

By the 1950s, the ethos of climbing itself began to shift. A new generation looked not up toward summits but outward along sheer faces. These early free climbers wanted shoes that felt, not just protected. When Warren Harding topped out on The Nose in 1958, and when Royal Robbins completed the Salathé Wall in 1961, their teams were almost certainly still climbing in stiff, lug-soled leather boots. But those ascents marked the beginning of a cultural and tactile turning point. The climbs were getting harder, the features thinner, and the old boots were starting to feel like blunt tools on increasingly delicate rock.

By the late 1960s and into the 1970s, this shift was happening on both sides of the Atlantic. Climbers in Yosemite, later dubbed the Stonemasters, and their counterparts on British gritstone began adopting and amplifying a practice already circulating in the climbing world. Manufacturers were tuning footwear the way mechanics tune engines, cutting away tread and resoling shoes thinner. Their smoothness increased surface contact on limestone and granite and showed that sometimes progress is just removing what gets in the way. Durability stopped being the main priority. What mattered was the idea that a shoe could transmit subtle signals from the rock, and that a climber who could feel more could climb more.

And that brings us to the edge of the next shift. By 1979, the sport had outgrown the old tradeoff between durability and feel. In the next installment, we pick up when Boreal completes the final prototype of the Firé rock shoe and the concept of "sticky rubber" enters the scene, turning friction from a side effect into the main event.